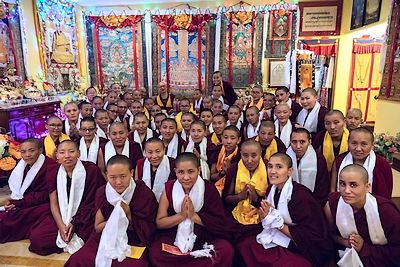

Monks and Nuns

In traditional, Buddhist texts there is a section called the Vinaya. It is mainly a set of disciplinary precepts describing the rules of life and vows for monks and nuns. Only persons initiated according to these Vinaya texts can actually be regarded as monks or nuns. However, over the centuries there have been interruptions in the transmission of initiations, causing individuals referred to as monks or nuns in popular culture, to not always be truly initiated. This can easily cause confusion.

According to the Vinaya texts, celibacy is always a part of a monk's or nun's ordination. For example, in traditional Japanese Buddhist schools there are actually no monks or nuns who are ordained according to the Vinaya. Celibacy is therefore not part of the rules they follow, while this is often expected. It may be better not to speak of monks and nuns in Japanese tradition, but of priests and referents. Until recently, ordination for women in the Theravada tradition, had been completely lost. The women who are often considered nuns, in white or pink robes, are in fact not, but are laypeople who have taken some additional vows (including celibacy).

A series of frequently asked questions and answers:

- Why become a monk or nun?

- How can a layperson practice the Dharma?

- Do people become monks and nuns to escape the harsh reality of existence?

- Is being ordained a painful sacrifice?

- Does one who is ordained disregard his family by leaving them?

- Sometimes I meet consecrated and laypeople who are bad or annoying. How is that possible?

- Why all the different colors and styles of robes?

Why become a monk or nun?

It is not necessary to become a monk or nun to practice the Dharma (the Buddha's teachings). Ordination as a monk or nun is an individual choice that everyone has to make for themselves. Of course, there are benefits to being ordained: as long as you don't break the precepts, you're constantly accumulating positive energy, even when you're sleeping. There is also more time for practice and less distraction in a monastery than in family life.

When people have obligations to their family, they have to spend a lot of time and energy looking after that family, earning money, etc. Children require a lot of care, and it can be difficult to meditate if they are playing or crying nearby. In a monastery, without the social obligations of a partner and family, it is simply easier to concentrate on study and contemplation.

How can a layperson practice Dharma?

Those who wish to practice Buddhism as a layperson can do this very well by trying to actually practice the Dharma and by training their minds. We can needlessly reduce our own energy if we are thinking: "I'm a layman. Listening to teachings, reciting and meditating is the work of monks and nuns. I don't have to do that. I only go to the temple, bow down, make offerings and pray for the well-being of my family." It is good to do these things, but most laypeople are capable of a much richer spiritual life, both in terms of knowledge about Buddhism and in truly incorporating it into their daily lives. It is very important that they follow the Dharma talks that are available and try to follow a series of lessons. If they do this, they will come to understand the real truth and beauty of the Dharma.

After listening to the lessons, the aim is to put them into practice as much as possible. Daily prayers or meditation practices are excellent. Sometimes lay students say: "My day is so filled with work, family and social obligations that there is no time left to do a daily Dharma practice." This is a sad excuse that just doesn't make sense. There is always time to eat: we make sure to never skip a meal. Just as diligently and carefully as we feed our bodies and always find time to do so, so should we feed our minds. After all, it is our mind that moves on to subsequent lives; it is our mind that carries with it all the karmic impressions of our actions, not our body. We do not practice the Dharma for the benefit of Buddha but for our own benefit. The Dharma describes how to create the causes for happiness and since we all want to be happy, we should all do as many practices as possible.

It is also very helpful and beneficial for the non-ordained to take the five lay vows for the duration of their lives or take the eight Mahayana precepts for special days, such as at new and full moons. In this way they can create a lot of positive energy. And it is positive energy that makes us happy. The responsibility for the existence and dissemination of Buddha's teachings rests with monks and nuns as well as with lay disciples who teach. If we understand the value of Buddha's teachings and want them to continue to exist and flourish, then we have a responsibility to learn and practice them according to our capabilities. It is also possible to take further vows, such as the bodhisattva vows and tantric vows. There are many historical examples of lay people who have attained high spiritual realizations. Hearing about their lives and following them can be inspiring to us.

Do people become monks and nuns to escape the harsh reality of existence?

Some people think, "Only people who can't make it 'in the real world' become monks or nuns. Maybe they have problems at home or did not do well in school or they are poor or without a roof over their heads. They live in a monastery and take vows only to have a roof over their heads and have an occupation." People who think this way look down on those who are ordained. However, this is incorrect. When a person becomes a monk or nun for that reason, the motivation is not pure, and such a person will rarely find the consecrated life satisfying. The teachers who perform the ordination try to carefully select the right kind of people.

People with the right motivation want to develop their abilities to control their minds and thus be able to help others.

The true causes of suffering are attachment, ignorance and anger. These attitudes follow us everywhere. They don't need a passport to come with us to another country, nor can we leave them outside the monastery gate. As long as we are attached or ignorant or angry, we cannot avoid our problems, whether we are ordained or not.

People who ask this question often think that a job, a mortgage and a family to care for are difficult tasks, and that they are the "hard reality of existence." However, it can be a much harsher reality to be honest with ourselves and recognize our own wrong views and harmful behavior. It is much more difficult to overcome our anger, attachment, and closed mind.

A person who recites or meditates cannot display a skyscraper or paycheck as proof of their success, but that does not mean they are lazy or irresponsible. We must make great efforts to change the harmful habits of body, speech, and mind; it is not easy to become a buddha. Rather than "escaping reality," sincere practitioners try to discover it!

From the Buddhist point of view, it is precisely those who pursue only temporary pleasures and wealth that are escaping reality, for they refuse to face the reality of death and the functioning of cause and effect (karma) and continuously seek meaningless distractions instead. In the Buddhist view, worldly people are lazy, because they do not strive to subdue their attachment, anger and closed minds, no matter how busy they are with their superficial worldly lives.

Is being ordained a painful sacrifice?

It shouldn't be. We shouldn't feel like, "I really want to do these things, but now I can't." Leaving negative activities behind should not be seen as a burden, but as a joy. Such an attitude arises after thinking about cause and effect and what you want from this precious human life.

When we take vows, whether it be the five lay vows or the vows of monks and nuns, we must first of all arouse this attitude: "I do not want to do these negative things anymore. In my heart I do not want to kill, steal, lie, etc." Sometimes in a certain situation we are weak, and we are tempted to do these things, but the precepts give us extra strength and determination not to do what we really don't want to do.

For example, we sincerely don't want to kill anymore. But when there are cockroaches in our apartment, we may be tempted to use a pesticide. Because we have taken the precept not to kill, we more easily remember that we do not want to kill. We are more aware of what we do and have more strength and determination to face and turn away from the disruptive emotions that negative activities can cause. In this way, precepts are liberating and not restrictive, for we free ourselves from the habit of following disruptive emotions and getting lost in harmful activities.

Does one who is ordained disregard his family by leaving them?

On the contrary. People who sincerely want to improve the world through their religious practice absolutely take their family into account. They understand that they will be able to lead others to eternal happiness through the path of the Dharma by creating the causes for future good rebirths and purifying and developing their minds. They realize that this is very beneficial for their parents and useful for society. Although they may not achieve high realizations in this lifetime, they have a broad vision and work for long-term happiness and salvation. A truly committed person thinks, "If I go on with my worldly life I will only create the causes for lower rebirths for myself and cause others to do the same. How can I help my parents in this life and in the next, when I do that? However, if I engage in the sincere practice of Dharma, my own good qualities will increase and I will be able to guide them and help them better.”

Just because ordained people leave their family life doesn't mean they reject their family or that they don't care about them. Although they give up the negative emotion of attachment to their family, they still appreciate the kindness of their parents and care deeply about them. Rather than limiting their love to a few people, devotees try to cultivate an impartial love for all sentient beings and see them all as part of their family as well.

Sometimes we come across ordained or lay practitioners who are evil and difficult to get along with despite their religious practice. How is that possible?

It takes time to really change the mind. Getting rid of our anger is not an easy process. We can understand this from our own experience: if we are used to losing our cool, it takes more than saying, "I mustn't do this" to make us stop. We must constantly do the right exercises for this. We must be patient with ourselves and likewise we must be patient with others. We all walk the path; we all fight against the inner enemies of the disturbing emotions and the impressions of past actions. Sometimes we can act strongly against it, at other times we are carried away by anger, jealousy, attachment or pride. Sometimes we see how closed our minds are; at other times we are blind to that reality. There is no point in judging and blaming ourselves when we succumb to the disruptive emotions. Likewise, it is useless to blame and criticize others when they do the same. Since we ourselves know how difficult it is to bring about inner transformations, we must also be patient with others. We're all trying, and we're not Buddhas yet.

The fact that practitioners are not perfect does not mean that the method that Buddha taught is not perfect. It means either that they are not practicing this method correctly or that their practice is not yet strong enough. In religious circles it is extremely important that people try to balance and accept each other's weaknesses. It's not our job to accuse anyone and say, "why don't you do your practice better? Why don't you control your anger?" Instead, we should think, "why don't I do my practice better so that their activities don't make me angry anymore? And what can I do to help them?"

Why all the different colors and styles of robes?

As Buddha's teachings spread from one country to another, it was natural to adapt to the individual cultures and their ways of thinking. All of this was done without changing Buddhism's essential essence and meaning. Therefore, the style of robes varies from one country to the next.

In Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma, etc. the robes are saffron-colored and sleeveless like the robes at the time of Buddha.

In Tibet, however, that color of dye was very expensive and scarce, so a deeper color was used there: a dark burgundy red.

In China, it is considered impolite to see the skin, so the robe was modified and now they use long-sleeved T'ang Dynasty attire. The Chinese thought that saffron was too cheerful a color for religious use, so the Chinese robes are often gray. The spirit of the original robe, however, was preserved in the form of the seven- and- nine-piece brown, yellow and red outer garments.

The way of chanting prayers in different countries also differs according to the culture and language of the place. Chinese stand while singing, Tibetans sit. The musical instruments also differ, of course, as well as, for example, the way of bowing down. These variations arose from cultural adaptations.

It is important to realize that these outer things are not Dharma. They are just tools that help us to practice the Dharma better according to the culture and place where we live. The real Dharma, however, we cannot see with our eyes and we cannot hear with our ears. We can experience the Dharma only through our mind. It is important to emphasize the real Dharma and focus our attention on that, and not on the superficial, outward manifestations that may vary from place to place.

See the next page: The spiritual teacher